- Home

- Sonja Livingston

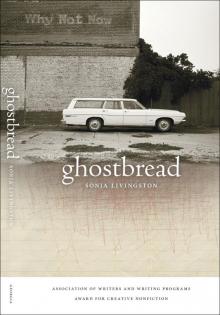

Ghostbread

Ghostbread Read online

ghostbread

WINNER OF

THE ASSOCIATION

OF WRITERS

AND WRITING

PROGRAMS AWARD

FOR CREATIVE

NONFICTION

ghostbread

SONJA LIVINGSTON

Paperback edition published in 2010 by

The University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

© 2009 by Sonja Livingston

All rights reserved

Designed by Walton Harris

Set in 10/14 Garamond Premier Pro

Printed digitally in the United States of America

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover

edition of this book as follows:

Livingston, Sonja.

Ghostbread / Sonja Livingston.

ix, 239 p.; 23 cm.—(Association of Writers and Writing

Programs Award for Creative Nonfiction)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-3398-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-3398-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Livingston, Sonja—Childhood and youth. 2. Poor girls —

New York (State)—Biography. I. Title.

HQ777.l58 2009

305.23092—dc22

[B] 2009009150

Paperback ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-3687-9

ISBN-10: 0-8203-3687-4

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

This is a work of literary nonfiction, based on experience and memory. Only names have been purposefully changed, and then in deference to those whose lives intersected with my own.

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-3750-0

To SONJA MARIE ROSARIO

and all the girls of Rochester, Buffalo,

and places in between

preface

When you pick up a pen, put it to paper, and let yourself go, certain words throw themselves at you, whole paragraphs come to you unbidden, entire passages stake their claim, refuse to be ignored. Even when you don’t want them. Especially when you don’t want them.

As a girl, I never talked about how I grew up. It was complicated. People might point fingers. My face might turn hot and wet and a hundred shades of red. Mostly, I was certain that I was alone in a way that no one would understand.

But as I sat in my first creative writing class, wadding up paper and waiting for something to come, the stories nudged at me, harder and harder, until finally, they made their way out.

I began to write. Of seven children who followed a mother as she flew around western New York like a misguided bird. How they flew and flew until they were sick from all the flying then landed flat and broken into the muggy slums of Rochester, New York. I wrote of living in apartments and tents and motel rooms. Of places where corn and cabbage grew in great swaths. Of the Iroquois on their reservation outside of Buffalo. About sleeping in shacks and cars and other people’s beds, and finally about a tiny dead end street in an overcrowded innercity neighborhood.

And as I began to share my writing, I learned that I was not so alone. While the specifics of my circumstances were certainly unusual, a child living without basic resources in 1970s America was not as uncommon as I’d once believed.

The western portion of New York State is a coming-together of various influences. The northern tip of Appalachia meets up with the easternmost notch in the Rust Belt. Poverty exists in many forms within a two-hundred-mile radius. It blooms quietly on Indian reservations, in old farm towns, and in cities seething with higher rates of crime and child poverty than New York City. It spreads like a bruise between Buffalo and Rochester, a stain just under the skin.

Writing helped me to talk about the places and people of my childhood and to connect with others, but in sharing, I inevitably encounter someone who does not believe.

“Rochester has no ghetto,” they say, or else they cock an eyebrow and say, “Reservations? So near us?”

So we’ll get into a car and drive out to a place, only to find that what was once barely standing has finally collapsed. Where for hundreds of years stood a behemoth of a house are now only trees. The old shack that once gave shelter to a brood of children has become vines. The gold-shingled two-story with a gangly lilac out back is just another vacant city lot. And though I can’t always recover the specifics (the houses or gardens or trees) of the past, the reality of such existence remains.

It’s there. For those who steer their cars off the New York State Thruway and interstates. The broken cities, the sprawling rusted landscapes, the huddled people.

They are all there.

I wrote this book because the pain and power and beauty of childhood inspire me. I wrote it selfishly, to make sense of chaos. I wrote it unselfishly, to bear witness. For houses and gardens and children most of us never see.

acknowledgments

Earlier versions of some material appeared as essays in the Iowa Review, Gulf Coast, Puerto del Sol, and Mary.

Many thanks to early readers of my work: Judith Kitchen, Karen DeLaney, Sarah Freligh, Paul Bond, Deb Wolkenberg, Sharon Pierce, and the Hilton HC (Laurie, Bonnie, Donna, Karen R., and Karen K.). I appreciate careful readings by Deanna Ferguson, Allen Galante, Gregory Gerard, Stephen Kuusisto, and Julietta Wolf-Foster. I am grateful to Gail Mott for her thorough reading, and to her and Peter Mott for so much more.

Thanks to my angels from New Orleans, especially Amanda and Joseph Boyden, Dinty W. Moore, Lisa Shillingburg, and Kim Bradley.

Rob McQuilkin, with his sharp eye and quick pen, greatly improved this manuscript and championed it against even greater odds.

Thank you to Kathleen Norris, AWP, and the University of Georgia Press, to family and friends, and most of all, to those represented in these pages.

Much love to Jim.

part one the get go

1

I know where I came from.

It must have been April or May of 1967 when he came through town, a vacuum-cleaner salesman with a carload of rubber belts, metal tubing, and suction hoses. Spring in western New York, it was probably a sunless day—he may have been chilled as he grabbed hold of his Kirby upright, walked to the door, and rang the bell.

She was a well-formed redhead with a dry-cleaning job and a house full of children to forget. She must have put hand to hip, flashed falsely shy eyes, and said something about not needing another vacuum.

He had full lips, and used them to throw a smile in her direction. And she, who was partial to full-lipped smiles, let him in.

He rang; she answered. She was hungry; he had a bit of sugar on his finger. He was tired; she provided a pillow for his head. Soft. Sweet. Easy.

Sometimes it’s just that simple.

2

I was late. Born in the wrong year, according to my mother. Though scheduled to clear her womb in 1967, I was mule-headed and did not exit my mother’s body until late January 1968.

The story was a good one. My mother swore by it. People clucked and laughed when she told it. Growing up, it made my birth seem special. Like I was cracked from another of Adam’s ribs or crawled from my mother’s womb fully-formed and armored, like some commonplace Athena.

I imagined myself made stronger by all that time inside her. As if twenty-eight extra days and twenty-eight extra nights pressed against the lungs could compensate for the lack of baby pictures, the lack of a proper last name, the lack of a daddy. As if four weeks could ever make such a difference.

We were all late, according to my mother. Except for her first, my brother Will, who was two months early, born backward and twisted. Breach baby. He almost didn’t make it, she said. The cord curled round his neck, threatened to pull him back into the womb. Keep him. Will was the only

one who’d surprised her—the one whose birth she spoke of with wide eyes and hushed tones. The rest of us were easy—forward-bound, fat-faced, and untangled.

And a month late.

She just carried her babies longer than most, she’d explain if you asked, and if you listened, really listened, you’d understand that it was my mother, not us, who was special—the way her body wouldn’t give up its pearls. She’d say it’s just a part of who she is, the same way she stopped any watch she wore, all that energy pulsing through her veins. Some things the body just refuses to share.

My mother told the stories of our births over and over, and made them bigger with each telling. We were her handiwork. So she talked about water breaking, the running of fingernails into wood grain, the cutting of umbilical cords. Her tales were rich in gook and detail. Nothing was left out. Except for fathers. They were ghosts that folded themselves into the edges of her tales, vapors that floated in and out of delivery rooms, with us somehow, but never really showing themselves.

3

I had no father, which sounds much more dramatic than it was. If I’d known girls whose daddies held them tight and gazed at them with so much pride it tore at the eyes, I might have thought that all girls should have such a thing. But I never knew such girls. And how can someone miss what she’s never had?

No, of this I am sure: a mother was enough.

A mother.

Like mine. One who was smart and pretty and drew horses so well-muscled and real they could gallop off the page. One who came from the state of New Hampshire, where blueberries grew in back of the house her father built and tamaracks stood in lines outside the window. New Hampshire, the granite state, whose bird was the purple finch and flower was the purple lilac and whose motto was live free or die, which is what she’d say if you asked why she made up her own rules about clothes and religion and men.

I’d ask, from time to time, why she didn’t do things the way that other mothers did.

“Why don’t you have a husband?”

“Why don’t you make regular meals?”

“Why don’t you teach me to do up my hair?”

In serious moments, I’d ask such questions, and she would listen without showing it, her small hand resting on the spine of a book. I could see by the way she squinted her eyes that she was thinking, so I’d wait until she looked up, eyebrows raised, as though surprised by my presence. As though she’d just remembered me and my questions. She’d look at me hard, and say, “Live free or die—I’m telling you girl, there’s no other way to be.”

4

My favorite person should have been Carol Johnson. Carol’s voice was like gravel, her words came out slow and sifted through the cigarette perpetually pressed between her lips. She was as thick-fingered as any man, but kind. And painfully generous. She had four kids of her own, but managed to treat me like I was special. Carol said beautiful things about my hair and eyes, and when she ran out of things to say, she gave me things. Cupcakes and colored scissors and a glossy black purse with a gold metal snap that she wrapped up for my fifth birthday.

I loved that purse! Its shine and promise. I opened and closed, opened and closed it, delighting in the cushioned clicking of the snap. I clicked it hundreds of times—until I tired of it, or it wore out.

Once the snap lost the hold it had on me, I began to wonder what to fill the purse with. For the first time, I wondered where money came from. I looked into its gaping black mouth and worried over how to feed such a thing. When I asked, my mother laughed.

“Where does money come from?” she cackled. “You be sure and tell me when you find out.”

Her laughter did not stop me. I asked my question over and over, until it lost its freshness and earned me only dark stares. I looked into the black interior of the purse and began to see its emptiness as a weight to be carried.

I loved the glossy little accessory, but couldn’t enjoy it, and in the end, Carol took the purse back to stop my worrying.

To give and take with such love is rare—so naturally, it was Carol I should have loved most.

Or my mother.

But it was neither. Instead, it was the woman with the owl earrings. A teacher at the day care center who made a seat for me of her lap. She helped me with my letters and held me for as long as I needed. I’d sit there as often as I could, pushing my head into her chest, looking up at her earrings—silver dangling owls. A few strands of silk-brown hair fell from her ponytail and I’d take them between my fingers while she held me. I’d plop a thumb into my mouth and stare into those earrings. Wise old owls. Silver and jangling. Moving as she laughed.

5

Something big happened.

I found five dollars and discovered what it felt like to swallow the sky. The money was folded on the sidewalk in front of our apartment. I saw its color first, a tight rectangle of green lying flat against the gray walk. It was sitting there like a gift, so I picked it up and handed it over to my mother who thanked me, hugged me, adored me.

“Honestly,” she said, “I didn’t know how we would eat tonight.”

To be taken by the hand to the corner store and allowed to choose a special candy—that’s something. To be talked of with gratitude and pleasure, my name coming out of her mouth like a song. To be lifted over the shoulder, made to feel like the sun and the moon—it was almost too much to bear.

But there was a twist. There’s always a twist.

Because when things are found, it is also true that they are lost, and the five dollars that made me family hero and benefactress of macaroni and cheese dinner was the very same bill dropped by someone else. So when my mother lifted me up to the counter, I smiled and let my fingers skim the ruffled faces of penny candy, but remembered the Brownie troop that had passed our place just minutes before my find.

I selected my candy reward and thought of the double-file line of brown-uniformed girls, giggling in their cocoa-colored berets, one of them not knowing she’d lost her money, one of them looking, digging perhaps, into her tiny brown pouch the exact moment the atomic fire-ball settled into my mouth.

6

Finding five dollars wasn’t news for long.

Other things happened.

Big things.

Three girls were killed. Right here, in our city. Rochester, New York. They were put into the ground, those girls. Buried under flat stone over at Mount Hope, lying silent beneath the red earth and wild violets of Holy Sepulchre. Something terrible happened to them. Something my mother spoke of with hands over her mouth.

“They were from the city,” was all she’d say, “from the city, poor, and Catholic.”

Like us.

She never said it, but it was there.

Each had first and last names starting with the same letter. Wanda Walkowicz. Carmen Colon. Michelle Maenza. The man on the news said they were found with half-digested cheeseburgers in their bellies.

Why had those girls let him feed them?

The mystery of their trust plagued me more than the mystery of their deaths. Here’s what I decided: I wouldn’t eat a thing if he came for me. I knew my letters, could spell out my name, and my mother had told me twice already that my initials were not doubled, so there was that to hold on to. “There’s nothing to worry about,” my mother said and tried to sound sure of things, but I knew by the way she told us to stay by her side that she was scared too.

One of the girls had lived close to us. Michelle was in the third grade with my brother one day and the next, his classroom had an extra desk.

Lucky for me my initials were mismatched. Good thing my mother mixed things up. And the girls he took were nine or ten, while I was not yet six. Still, he might have run out of double-initialed girls or changed his mind about the age he wanted. I thought of such things, but most of all, I worried about my hunger, that he might sense it in me, that I might forget myself and eat whatever he offered.

So if he came for me, I knew just what to do. I’d decided on the exact cupbo

ard to ball myself into. And if he found me there, I knew how to protect myself. I’d keep my mouth closed, and no matter what—even if he pried it open with big angry hands—I would let nothing pass.

7

Sometimes we’d explore.

My mother and her children walked in a line through the neighborhood, a ragtag group of boys and girls, arranged by descending height. We’d crisscross the streets in the northeast section of the city, resting along the way until we found ourselves on the sloping green hill near the softball field on East Main and Culver. Six kids, grubby-fingered and pushing through the slippery pile of books fished out from the twin Dumpsters that stood like sentries outside the high school. So many gloss-covered books were discarded that they slopped over the tops of the Dumpsters and fell into our hands.

“Who would throw these away?” My mother’s eyes grew with the prospect of all those words.

She pushed her red-brown hair into a knot at the back of her neck, sat on the grass, and entered a book so softly that we barely spoke. She only answered after we asked twice if it was okay to chew on purple-headed clover.

It was warm, with a breeze, and we watched as three Vietnamese men pulled June bugs from the small trees lining the sidewalk. They pulled the bugs from the air, flattened the shells between finger and thumb, then tossed them into the plastic buckets they carried.

“They’ll eat those bugs,” someone said, and we laughed and chewed the nectar from clover.

We lounged, spread out on the grass until the sun lowered and our skin cooled. Even then, we didn’t want to let go of the day and tried lugging armfuls of the books home. In the end, there were not enough hands and arms to carry all those books away. But the want was there.

Ghostbread

Ghostbread Queen of the Fall

Queen of the Fall